Diagonaldi

Very well executed

CommentsXp

Best movie ever!

CrawlerChunky

In truth, there is barely enough story here to make a film.

Twilightfa

Watch something else. There are very few redeeming qualities to this film.

Robert J. Maxwell

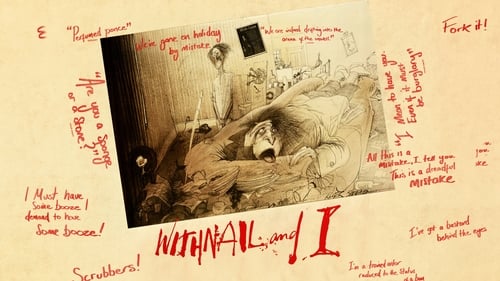

There's something wrong with me because whenever I hear a film referred to as a "cult movie" I avoid it. "Withnail and I" was called a cult movie but it's an exception because it's actually pretty good. You have never heard insults and curses with so much elegance and filigree. They could tear a hole in the space/time continuum.Richard Grant and Paul McGann are two young aspiring artists (of one sort or another, maybe acting and writing) living in a London flat that's so sloppy, so ill kept, so dishabillé, so DESECRATED, that it looks almost like my humble abandoned railway car. Both are neurotics in the same way that both are artists. Grant is Withnail, tall and skinny, and McGann is the "I" in "Withnail and I." The former is given to an excess of alcohol from time to time, while the latter has anxiety attacks on a regular basis. "LOOK -- my THUMBS are going weird!" They're visited by a doper friend who has a cool exterior, what can be seen of it beneath the fright wig, and a speech impediment that renders even his slowest, most ominous threats harmless as a child's. "If I ever 'medicined' you, you'd think a bwain tumor was a birthday pwesent." Withnail and I shake down Withnail's gay and wealthy uncle (Richard Griffiths) for the key to Griffith's weekend country house, which hasn't been used in years and turns out to be in ramshackle shape. Griffiths appears later in the film when he visits the two lads at the house and puts moves on McGann, scaring McGann to death, but Griffiths' best lines show up during his introduction. He says to his nephew, "Would you pour us a sherry, dear boy?" and then leaves the room for a moment, during which Grant hastily grabs the bottle and wordlessly chugalugs a couple of glasses worth. They begin discussing gardening. Griffiths love cauliflowers. "There's poetry in the cauliflower. Roses are the prostitutes of plants, just sitting there waiting to be pollinated by bees. But vegetables in general are noble. There's nothing like a firm young carrot." (Paraphrasing there.) The story weakens a bit at the country estate, a filthy place, and the weakest segment is Griffiths' visit that introduces a touch of pathos.Finally, the duo return to their London flat to find it occupied by the doper and his colossal black friend. Some of the humor is kind of subtle so I'll point out an instance here. Throughout the movie, the two white guys have a tendency to Jimmi Hendrix and his blackish hard-rock electric guitar. When they get home from the country. Withnail and I find the bathtub occupied by the strange black guy with the Afro and he's listening to The Beatles, "While My Guitar Gently Weeps." It's funny, see. The white guys listening to black rock and the black guy listening to The Beatles "White Album"? No? Am I committing the Texas sharpshooter fallacy? At the end, sadly, Withnail and I split up, for reasons not made too clear. And Withnail, the actor, addresses a zoo with wolves and comes out with some lines from Hamlet, which I am about to quote: "Recently, though I don't know why, I've lost all sense of fun, stopped exercising-the whole world feels sterile and empty. This beautiful canopy we call the sky-this majestic roof decorated with golden sunlight-why, it's nothing more to me than disease-filled air. What a perfect invention a human is, how noble in his capacity to reason, how unlimited in thinking, how admirable in his shape and movement, how angelic in action, how godlike in understanding! There's nothing more beautiful. Men don't interest me. No-women neither, but you're smiling, so you must think they do. We surpass all other animals. And yet to me, what are we but dust? " But Withnail's reshaped the lines so that the quotation ends with the dismal "dust." Then he tromps off through the torrent of rain. It would have been better, more filled with irony, if he'd just ended the quote with "There's nothing more beautiful." I mean, after all, why paint the lily?

SnoopyStyle

It's 1969 London. Withnail (Richard E. Grant) & I (Paul McGann) are a couple of struggling actors living in a rundown filthy flat. They struggle to find the money for heat. Withnail is a constantly complaining drunk. I suggest going to the cottage of Withnail's gay uncle Monty (Richard Griffiths). They are visited by Danny the local drug dealer.It's a dark comedy. I don't know why but a lot of it didn't connect for me. It's possible that I don't get half of the references. It's also possible that I don't find Withnail funny. Grant is doing a big performance but not a funny one for my taste. I also don't understand their 'friendship'. The homo humor wears out for me. It is however undeniable that Grant shows the power of his acting in his film debut.

chaos-rampant

This takes a pretty ferocious look at modern life, a gray British life to be sure but it more generally directs its disillusionment towards a global generation that could even faintly remember the Stones and Vietnam, or at least grew up on that certain charged dream.It is about the dissatisfaction bred by city life, the misery and sense of sickness, more pronounced of course. Now we have settled down, we are beginning find transcendence in this world. Two down-on-their-luck actors take a trip to the countryside, there fail to find much cleansing and report back to normative life, Withnail to return to his hazy half- life of drinking and vexation, the narrator to go on to a 'normal' life.Their groundlessness with all its freedom has no reflection merely anxiety and madness, and finding an anchor, as it happens in the end, means becoming an actor on the stage, assuming again the old narrative. Sure it is hilarious to watch, but deep down it is a tremendously sad film.Here is where another quality of the film manifests, British. The Brits are trapped in a historical narrative, anchored in Shakespeare and the old empire. Their films when they channel that self are verbose, logical, theatrical, hardly visual outside a square narrative space. Smart, expertly narrated, impeccably acted; but hardly what I'd call contemplative.Lawrence of Arabia could only find contemplation in a desert that was precisely somewhere else, by adopting a new self for whom that desert could be an uncertain abode. For Dennis Potter, closer to my taste, the encounter with the viewer who looks back at himself happened in old songs and movies.So when the Brits rebel against that which is so ingrained in them, story, the results generally tend to be thin. Merely squashing story is liberating enough, refreshing of its own. This is not so thin as the Pythons but still in a similar vein of situational disorder, skidding from one prank to the next. Implicitly, however, the filmmaker who also wrote this, knows that he is not doing a collection of skits. The film's title is a clue. There is an I here for whom the story exists as both world and hazy recollection. A writer, one of the two actors, is our troubled narrator, Withnail a sort of fractured self lost in delirium and outgrown in the end.So we have this British rebellion against the yoke of narrative in a clear way. Everywhere they go they become actors, they constantly reinvent themselves, imagine narrative, you'll see this in every situation from the scuffle in the pub early to the poacher who is out to kill them.And this yields both comedy and inner pain, coming from a sensitivity to the cruelties of normalcy. It's as if life cannot be approached simply, the absurd spectacle reconciled with, say a poacher with eels down his pants—it is to them a source of fear and vexation precisely because it doesn't make much apparent sense. This gonzo style obviously emulates Hunter Thompson, in fact the promotional material for the film are designed in Thompson's vein by his cartoonist since the Kentucky Derby days, Steadman. Gilliam in his Fear and Loathing went overboard in trying to actually portray a drugged perception, but it was his way of preserving the essence of a world at a certain remove and the self tearing at the viewing walls.It fits here like a charm against the mannered world of the Brits until the silly bit with the gay uncle derails the second half—from that point because suddenly the urges make sense, there is story and it is pretty unambiguous and certain. So unwittingly it falls back to that British trap that it was trying to claw its way from.The filmmaker would return to Thomson with Rum Diary, this much better captures the spirit.

stephparsons

This is the second time I've watched this movie - with a mere 20 year gap in between viewings - and I can honestly say it's as brilliant as I remembered and still made me want to live the life of a reprobate, booze-swilling, drug-chomping, out of work actor, lounging around in a smoking jacket or madly running round the Welsh countryside being chased by angry locals- despite the fact that that romantic idyll is so thoroughly de-bunked in 'Withnail & I'. For some reason, the film can't help one view Withnail and Marwood's 'bohemian' lifestyle through rose-tinted spectacles.Withnail, an unemployed and (for all intents and purposes), unemployable actor is an inspired act by Richard E. Grant and Marwood, his long suffering friend, is portrayed skillfully by Paul McGann. The two degenerates have sunk to the very depths of squalor and despair and live surrounded (and drowning) in their own filth and detritus. Withnail is the perfect stingingly aloof, uncaring 'angry young man', immersed in self-destruction and the very epitome of a self-destructive, sneering, middle class intellectual that only the British could engender. Marwood cares a mite more and eventually becomes somewhat concerned about their situation: the copious amounts of drugs they ingest, the money they don't have and the terrible state of their health and surroundings. Facing the kitchen sink (and the horrors that lurk therein) appears to be the turning point when they both realise they have 'have to get away from it all'. At this point it would be very remiss of me not to bestow praise upon Ralph Brown, who plays Danny, the stereotypical monotone, ever-stoned, ever-present drug dealer, who, while appearing and sounding like he doesn't have many brain cells left, actually provides a quirky brand of mindfulness, wisdom and calm in the face of his clients' drug induced bouts of terror. When things can't get any worse for the hapless duo, Withnail remembers that his rich Uncle Monty has a 'cottage' in Wales that could be just the ticket for their escape from the filth, drugs and self induced paranoia that have become the very essence of their dissolute London life.The thing about 'Withnail & I' is that the plot really doesn't matter; it's all about the characters, the dialogue, the milieu and the emergence of a generation of 'drop outs' who just don't care about societal conventions and yet hold on to a strong sense of self-entitlement; as such, this movie effortlessly provides entertaining, hilarious, 'black' and addictive cinema. It captures so many quintessential elements of British culture from the all too obvious class system, to the rolling countryside, stone fences, and patchwork fields, to the emerging culture and the ways in which characters of Withnail and Marwood's ilk attempt to rebel against the social order. Despite their intellectual prowess, the two miscreants have no practical skills whatsoever, resulting in much hilarity (for the viewer) as they lurch about the countryside, supremely inept at 'living off the land', or even making it to the shops. Uncle Monty, played by Richard Griffiths, is perfect for the part and his lascivious pursuit of Marwood results in the ultimate bedroom farce.Withnail and I is a cult classic, from its excellent and fitting soundtrack to its perfect depiction of the privileged, over educated and willfully unemployed generation of that time. If you appreciate good movies and haven't seen it - YOU MUST!