IslandGuru

Who payed the critics

Breakinger

A Brilliant Conflict

ChicDragon

It's a mild crowd pleaser for people who are exhausted by blockbusters.

Ortiz

Excellent and certainly provocative... If nothing else, the film is a real conversation starter.

eldiran-24234

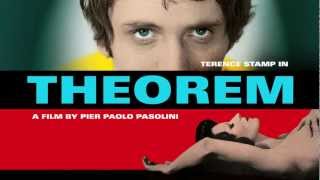

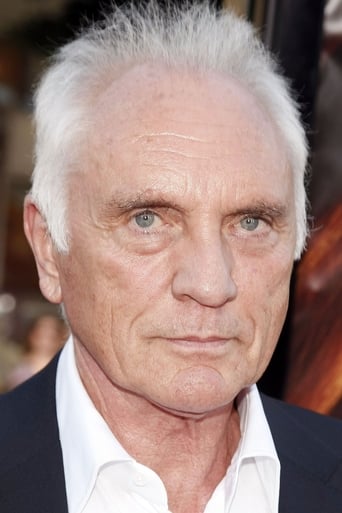

As always with Pasolini, we get clumsy acting, dialogue and camera work, though here the story is so important and vital that I've given it more stars than it aesthetically deserves. A stranger appears within a wealthy Italian family, is seduced/seduces each of them--old and young, women and men--and they are all changed by his (its) presence. Though Terence Stamp is perfect physically for the androgynous/bisexual angel, he is a bit adrift among Pasolini's amateurish melodramatic and kitschy handling of film-making. I recommend it ONLY for the brave and rare portrayal of Connection/Love as genderless

christopher-n-robinson

Pasolini has created a more serious and complex version of the 1930's classic "Boudu Saved From Drowning" in which a mysterious figure descends on a household of bourgeois people in Milan, a household whose members struggle with all sorts of psychological and religious issues. In this case we have no idea who the mystery person is, indeed the family just seem to accept him. Over the course of the film the stranger manages to have sexual and loving relationships with everyone from the maid to the father of the household. The young son struggling with homosexuality, the maid caught up in a virginal religious state, a besotted young teen daughter, the mother with unfulfilled sexuality and the father struggling with his bourgeois attitudes to human capital and homophobia. The stranger disappears as mysteriously as he arrived and the family goes into a perverse decline, other than the son who becomes an artist influenced by Francis Bacon, the English artist who represented many homosexual images of his own relationships in his striking art (as seen in a book featured in the movie). Each member seems to have been touched by some strange religious experience, left to come to terms with their perversions and fears. The film is often seen as representing the trans-formative act of religion with some being touched by the hand of god and others continuing their worst attitudes and behaviour. The father leaves his factory to his workers, the teen goes into a catatonic state, the maid becomes a healer and mystic destined for an unusual death, the son a talented artist and the mother increasingly and uncontrollably lustful despite constant religious images impinging on her senses. The father symbolically casts off all bourgeois elements by stripping naked in public. Video references keep crossing to some strange desert landscape, whose meaning only becomes apparent at the end like some scene from hell. What is often ignored is the camera-work which is often tracking across the top of many scenes almost as if it is searching for some truth. Really an amazing movie requiring a lot of work and thought from the viewer.

Stanley-Becker

The prologue of this movie is actually the epilogue. Pasolini emphasizes the artistic freedom to turn the world inside out and fictionally destroy all conventions. In a pseudo-documentary vignette intellectuals debate with the new industrialists {formerly "the workers"} and future plutocrats as to whether they will become subsumed by the bourgeoisie as a result of being inevitably corrupted by the trappings of wealth and power.In the jump between the main story and the prologue a motif, {repeated throughout the entire movie}, of the Hebrews wandering in the wilderness, hoping to find the Promised Land, is insertedWe are introduced to the nuclear family in its bourgeois construct as an Industrialist with huge factories and a magnificent Milanese villa, his trophy wife, a beautiful female, sybaritic, vacuous and fashionably attired and coiffured, as befits her class, their son Pietro and daughter Odetta. All of them are illustrated as typically bourgeois, self-satisfied and complacently entitled to lead their lives empty of meaning. All bourgeois households of their class have servants and the religious peasant Amelia runs their household.Pasolini then has a metamorphic agent, the boyish Terence Stamp, enter into their idyll. A cypher for the creative force of the auteur Pasolini himself, "the boy" insinuates himself into the individual lives of each of the five personae in the household. First, for no explicable reason other than the sexiness of his appearance, {Pasolini's homosexuality focuses on Stamp's prettiness and young slender physique}. Stamp's personality is quite reserved and introverted, so although he is seen to be reading the iconic gay poet Rimbaud, and playing the fool in a boyish way, we are never quite convinced of any intellectual passion. The five seductions are all carnal, starting with the peasant Amelia, who is overwhelmed by Stamp's "aura" and, initially trying to avoid her "fall" by attempting suicide, succumbs to her desire for sexual congress with "the boy". In quick succession "the boy" inducts the younger son into the homosexual life. Here the thought occurs that a typical initiation into homosexuality by the older man would most likely be Pasolini's personal narrative, especially, as the story develops we see the son overcome his anguish by sublimating into the arts, as Pasolini himself, did. Next "the boy" is seduced by the mother and then the daughter pulls him into the bedroom. Finally the heterosexual father {in a typical gay fantasy "all straight men are potentially gay" } is seduced by "the boy". Having performed his role of alchemical mischief we are introduced to Tolstoy's novella "The Death Of Ivan Ilyich" when as if enacting the final chapter, the father falls ill and "the boy' takes his legs and holds them above his head giving him relief - it should be noted that Nabakov lectured on this work stating that Tolstoy considered bourgeois hypocrisy to be a moral death or suicide of the soul.Then, suddenly "the boy" - the revolutionary agent of transformation - announces his abrupt departure {this takes place almost exactly half way into the movie}. Like the aftermath of a bad L.S.D. trip, {Pasolini created this movie in 1967 at the height of the 60's revolution}, the confusion and dismay of the five individuals are the necessary results of picking up the pieces, and living a life with new values, and the meaninglessness of the past.Of the five the most personal is the son Pietro, who leaves home to take the path of the artist {Rimbaud's calling} and become a painter {deeply inspired by a coffee table art book of Francis Bacon}. He muses that now that his past delusions of normality were shattered by his realization of his homosexuality, he must embrace his difference and become a creative power himself. He becomes a painter and paints on glass reminiscent of Duchamp's "Bride Stripped Bare" - he goes through many changes and humiliations, eventually restoring his equilibrium and health, by realizing the inconsequence of his life in relation to the universe. Here you have Pasolini's personal odyssey integrated into the story.As to the other players, Amelia the servant returns to her country roots, where she becomes an austere penitent, and performs the Catholic miracle of levitation, only to be buried by an old peasant woman {played by Pasolini's mother} and once again with reference to Tolstoy's "Death of Ivan Ilyich" she declares that she is not dying but acting out of sympathy for those that are still living in moral death, aka the bourgeoisie. The mother in true homosexual style becomes a woman driven to find young boys { as in gay "cottaging", rent-boys, etc,}, and has anonymous sex with them. We leave her in a state of ungratified anguish. Odetta, the daughter {described by her mother as "caught up in the Cult of Family"}, allows her life force to seep away, while the father gives away his factories, and strips himself naked, ending up like his wife, wandering in the wilderness with no hope of finding the Promised Land.Another peculiarity of this beautifully framed cinema is Pasolini's gay framing of the male crotch which is in contrast to the usual Hollywood focus on the female mammary, buttocks and legs. There is also some clothing fetishism with the camera lovingly gazing at the male Y-fronts. {underpants}At the end of the explication of a theorem "Q.E.D." is affixed "that which has been demonstrated". I recommend this movie to those that are interested in the art of the 60's, gay art, revolutionary politics, and Surrealism in cinema. Its a mind blowing experience!

prekdahl

After seeing this movie I was very confused until I read an interview with Pasolini from 1969. In it he said, "I leave it to the spectator…is the visitor God or is he the Devil? He is not Christ. The important thing is that he is sacred, a supernatural being. He is something from beyond." When asked if the members of the family were in some way improved by their encounter with the visitor, he said, "Only in the sense that a man in a crisis is always better than a man who does not have a problem with his conscience. However, the conclusion of the story is negative because the characters live the experience but are not capable of understanding and resolving it. This is the 'lesson' of the movie -- the bourgeoisie have lost the sense of the sacred, and so they cannot solve their own lives in a religious way. But the servant is a peasant, really a person from another era, a pre-industrial era. That is why she is the only one who recognizes the visitor as God, why she alone does not rebuke him when he must leave. When I say God," Pasolini quickly adds, "I do not mean a Catholic God. He could belong to any religion, a peasant religion. All religions are really peasant religions. That is why religion is in crisis today. We are passing from a peasant world to an industrial world. But a world does not die, so the peasant civilization lives within us, buried within us. It is buried, along with the sense of the sacred, within the factory owner and his family in 'Teorema.'" ... "The father almost does (learn from his truly religious experience). He takes off his clothes and, like Saint Francis, leaves all material things behind. When he reaches the desert, which represents the ascetic life he has been trying to gain, he is not capable of living a mystical experience, as Saint Francis was, because he is historically made in another manner. He arrives almost to the limit of being saved, but he doesn't make it. It's very important that the middle-class sees its own errors and suffers for them."I would have to say that the movie is a failure, since I think it would be pretty much impossible for a viewer to grasp that interpretation after seeing the movie once, without exposure to Pasolini's thought. However, it has some beautiful and haunting passages, and the movie stays in your mind for a long time after you see it.