Linbeymusol

Wonderful character development!

Incannerax

What a waste of my time!!!

GamerTab

That was an excellent one.

Stephan Hammond

It is an exhilarating, distressing, funny and profound film, with one of the more memorable film scores in years,

framptonhollis

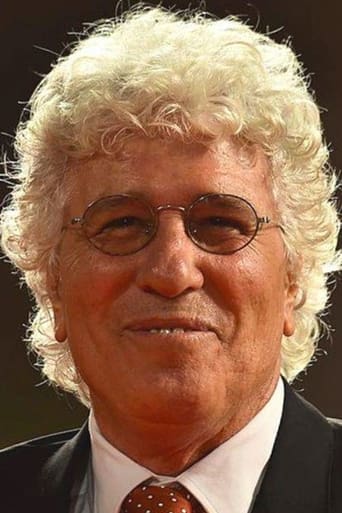

Based on a selection of stories from Giovanni Boccaccio's bawdy classic "The Decameron", Pasolini's successful and brilliant film works as a celebration of life, love, and sexuality. It's filled with moments of playfulness, joy, and laugh out loud humor. It also contains a fair share of somewhat tragic and dark elements-but, in the end, the film left with a great smile on my face.As a person who loves to laugh, I can assure you that "The Decameron" fulfilled my love many times throughout. It's hilarious- containing a sense of humor that ranges from crude to clever and from dark to light. It's one of the funniest films I've seen in a while.However, the film should also come with a warning, due to it containing some highly explicit sexual content. Practically every story told is sexual in nature, and some of them can be downright offensive depending on your beliefs. Of course, I was not at all offended by the sexual content in this film-even if I was a little shocked every now and then. But with that brief shock quickly came the relief of laughter, so I do not at all mind!"The Decameron" is wildly entertaining and funny-see it as soon as possible!

chaos-rampant

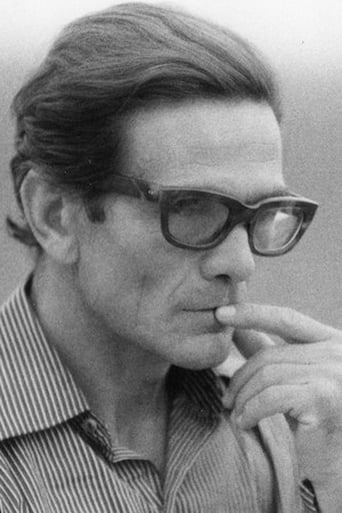

Pasolini is the only one of my cherished filmmakers who does not have a film in my list of greats, a weird thing. I love how he makes films but the main narrative thrust as carried in the long arch is usually so obvious, so extrovertly Italian, exposing modern absence of purpose in Teorema, human self-delusion here, that it seems like something we always knew. But he is a master of sculpting cinematic air, and this is a truly intelligent work of the medium, and not for any point it makes for sexual freedom or against religion.A few of the individual joys first, because he is so joyous to watch. The faces he finds, such astonishingly expressive Italians. they are not actors in the ordinary sense, they do not mask deeply troubled soul in the coy way of puritans like Bergman. They are human sculptures, each one seemingly handpicked as exuberant fresco of earthy, toothless mirth. His sense of place is naked, unadorned, discovered; unlike so many Merchant Ivory or Hollywood period pieces, I feel like I inhabit this world. His camera, again unadorned, even sloppy at times, but as revelatory as anyone's. In all these he teases the same spontaneous quality, that is what gives his work a certain careless air; but that is being carried by inspiration, instead of fixating on appearance. As honest as it is vital, because it was not excessively tampered with. He does not impose, paint beauty from the outside, it inwardly springs from air, from the flow of tangible emotion in tangible space jolting us into direct experience. Herzog could do it while being magical, few others. The film is a comic-book, an operabuffa in its narrative, but it's not without gravity that is life, nor is this the same as that tired business of 'realism' favored by the unimaginative like Nolan.Where it really soars is in the overall gaze, however pleasant, it is the gaze that elevates this to required viewing for me.All you need to know about the film is that it is in the form of thematically linked stories, centered in medieval Naples with rascals and scoundrels caught in mischief, often sexual. It is both funny and poignant, a film made for the same rowdy people it depicts. As said, the deeper purpose of the work is so readily available, show the marvelously flawed human being in all its buffonery and self- delusion, we may be inclined to think it 'small'. I think the problem is largely ours, myself included—we often mistake complexity for intelligence, reason with words instead of seeing the formative fabric.So this isn't complicated in what it says, but it is some of the most intelligent stuff I have seen.Look at the film again. In each story someone is being deceived, as are we watching a film. In each story, as in the overall film, the lie or deception reveals a more penetrating truth about self. Various selves pursue truth (linked to freedom from the norm), sometimes against the restraints of the story, sometimes killed by the story, sometimes negotiated to be a part of the story. So the easiest thing to do, what many crass minds would do, is to emphasize the strongest emotion, despair in one story, hypocrisy in another, and pull on that to draw audience reactions. We'd still have pretty much the same point, human buffoonery.It's all in Pasolini's multifaceted expression; in the first story with Andreuccio who came to buy horses, the poignant, ascetic lesson of 'thank god for losing your money' is uttered by two sneaky louts, so registers as both guidance and deception; in the story with the fake deaf-mute boy in the convent, the head nun deludes herself with the nonsensical miracle but simply oozes sexual joy as she rushes to ring the bell; in the story with two young lovers discovered the morning after sex by the parents of the girl, there is obvious hypocrisy by the father but everyone in the end happily gets his heart's desire; in the story with the illicit Sicilian boyfriend, we have both a sense of genuine bonding in the grove among the boys and awareness of its duplicity.The apotheosis, the most emblematic instance, is perhaps the cuckold potter; we get once more both the obvious duplicity, being cheated on, but also the ecstatic, enigmatic laughter of the divine fool who is each of us.See, Pasolini could point out social wrongs, or just plain stupidity, as well as Godard, but he could not afford to be a sweeping fool. Remember, he was a communist expelled from the Party in his youth because of his homosexuality—the best thing that could happen to him as an artist.What he does here is the same, a truly gentle soul. He sketches very simple desires, then bit by bit he challenges the simplicity of our logical leaps in dealing with them, leaps over unfathomable soul. The nun's miracle is nonsensical, but that is her way of coping with newfound joy. Who's to condemn her? Who, not being able to see her ecstasy, would be so dumb as to point out the fallacy of the miracle?This is real intelligence folks, the foundation of it. Seeing through the illusion to the self that gives rise to it, this being real freedom from the norm.

Nazi_Fighter_David

This is the first of Pasolini's three feature-film adaptations of obscene tales of antiquity, the other two being "The Canterbury Tales" and "The Arabian Nights." It contains ten of Boccaccio's most famous tales… The bawdiest story concerns a merchant who back-doors his partner's wife by promising to tell her his secret of turning a woman to a female horse and back to a woman again...The tale of the two lovers sleeping together on the terrace is quite nice and very erotic, but the most hilarious one involves a young man who pretends he's a deaf mute in order to get into a convent... Once inside, he discovers that the sisters are very curious about all the excitement the world has made over sex and want to find out if it is worth it...The stories are quite funny and the acting is adequate especially for non-professionals… But the film's charm is in its unrefined energy…It spends as much time showing nude men as it does showing nude women, which was quite unusual for its time

Cristi_Ciopron

In Passolini's synthesis, or blend of realities and fantasy, the realistic intention is very discernible and underlined: it is obvious he meant to give a taste of the Middle Ages as he perceived that epoch, and as he thought things looked like. Hence the flavor of his adaptations—the depiction of a world that is weird, loony, wild, brutal, and evidently godless. He tried to delineate a world that lives out of its own instincts and animal robustness in the biological accepting. It is, needless maybe to add, a leftist reading. Passolini's dire fantasies of orgy and brutality and sacrilege seemed to find a very propitious ground here. The sadness, the intended, meant, deliberate sadness of this movie is tearing-it expresses the desolation and emptiness of a devastated world, witnessed but not cured by an artist's testimony; the aesthetic credo has only a symbolic and ultimately personal value. Not the physical joy, nor the hedonism or sexual beatitude or merriness is at the DECAMERON's world heart—but the sadness. This sadness does not come from a century devastated by fear, anarchy and insecurity—but rather from within—as it is it, the named sadness, who molds the exterior world and enhances and colors the perception. Sad and almost desolate movie; atheism consequently explored and brought to its final deadly conclusions. Passolini was one of the artistically relevant artists. I abhorred SALO, I enormously liked THE DECAMERON, and I see the link between the both—Passolini' s drives, his need for sardonic Fascist (ultimately Nazi) fantasies. I do not mean to denounce him, but to show that what is here sadness is vehemence elsewhere; the man was a decadent, a corrupt man, not only witness but also part of the decay. His medieval fantasy, with its invented realism, is a devastated, sad land, a waste country of cold feverishness and cruelty—yeah, the impression here is one of dry cruelty and meanness and fanatic compulsions brought together by Passolini's sadness. I know that, besides the very obvious naturalism that is fundamentally symbolic, he also meant to bring the sad poetry of a bitter tenderness. Many take his adaptations for the opposite of what they are—for some kind of CARRY ON … popular comedies; on the contrary, they are mean decadent shows pierced by both Passolini's sadness AND his sense and representation of sadness. Aesthetically, his DECAMERON is quite rich; an atheist's credo, violent and grim and cruel and with that fanaticism and grimness and uncanny sharpness that make a better impression here than in SALO. The man was, I repeat, rather rotten and dirty. Nasty also, and twisted. The needed innocence is severely poisoned by sadness and despair. The DECAMERON, work of beauty and gusto, is poisoned by Passolini's radical despair and self—destructive drives; in his case, it seems unavoidable to bring his hidden, secret tendencies and his biography into discussion. He constantly harmed himself ;yet to pity him would be to abase and insult him. He deserves better. With the DECAMERON, he meant something—he meant his own sadness. Waugh spoke about people with the mind of a genius and the soul of an animal; of Passolini the opposite is true. Yet his heart finished by being severely damaged as well. The sex scenes are very good—they look like rough porn by a skilled maestro—the Perronella episode, or the one with the two adolescents. He was an injured, torn and twisted man (and of these things, either inner or exterior, one should speak without phony piety but without inappropriate indiscretion as well), moderately interesting (he was not as compellingly interesting as ,say, Antonioni or even Visconti or Fellini). As a personality, he was patently second hand . Yet he clearly was no Brass either. Put extremely simply, he had something to say; not only he could have had—but he indeed had. He created some things; his interest, therefore, as an artist far surpasses that as a man. He was closer than Visconti, maybe, to the grim, decadent, twisted Neo—Fascist porn aesthetics that will be illustrated by Mme. Cavani, by Brass and Bertolucci (and, of course, the many genre filmmakers). He had a temperament; he was a decadent (no one is structurally a decadent, I presume); these made his films what they are. His films show him mean, cruel, fanatic, and sometimes, as in the DECAMERON, sharp and inspired. When uninspired, he was maybe worse than Zeffirelli; when focused, he was far better, and infinitely sharper. If he, as a man, had any sense for his literary sources, this is far from obvious in his movies. In his thorough and mean atheism, offensive and narrow, he is as mean, delirious and fanatic as Buñuel. He hated the Holy Church as if he did this from Hell. He had not a drop of generosity in him. This tearing sadness is a valid and intended aesthetic result. The product of a decadent creativity and imagination, it is nonetheless imposing. This world of imagination is innerly voided, dramatically emptied and hence mechanical—feverish and cold visions of a waste humanity, excluded from life, left prey to its own base determinism; was this dream the world desired by Pasolini? There is something fundamentally ill and rotten and ailing in this world—almost the contrary of what the book meant. Not a trace of merriment—but a nihilist and sincere, true melancholy and desolation. The heart cut away from the life—and from the source of all life as well. The creation of a man untrue to himself as a man. These subtle values of Pasolini's daring vision are at least interesting as the picturesque and rough sex scenes.