ferbs54

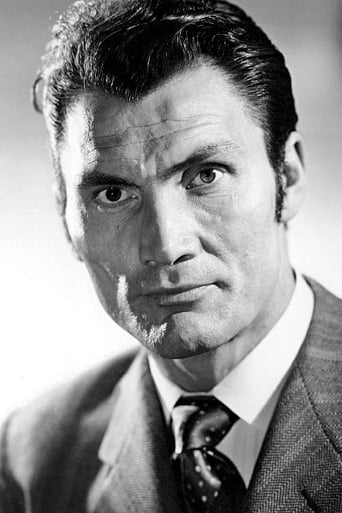

Released in November 1955, "The Big Knife" was, of course, hardly the first Hollywood film to throw a light on the town's seamy dark side. "What Price Hollywood?" (1932) had depicted the downward spiral of a Tinseltown director, "A Star Is Born" (1937) had given us an actor on an alcoholic slide, and "Sunset Blvd." (1950) had portrayed the destructive relationship between a former Hollywood actress and an aspiring screenwriter. In "The Star" (1952), viewers got another glimpse of an alcoholic has-been actor (effectively played by Bette Davis), while the 1954 version of "A Star Is Born" told its story with, arguably, even more punch and effectiveness. But none of those earlier films contained as much bitter cynicism, or as much caustic disdain of the studio system and its deleterious effects on an actor of integrity, as Robert Aldrich's "The Big Knife." Based on the 1949 stage play by Clifford Odets (Odets had already seen such plays as "Golden Boy," "Clash By Night" and "The Country Girl" adapted for the big screen), the picture pulls no punches in its depiction of a completely amoral studio system; one willing to stoop to any length--including blackmail, bribery and even murder--to ensure that those box office profits keep rolling in.The film tells the story of a hugely successful Hollywood actor named Charlie Castle (nee Cass, and splendidly portrayed by 36-year-old Jack Palance). Over the course of a roughly two-week period, we get to know of the problems that have lately been tearing Charlie apart. His wife, Marion (Ida Lupino), is desirous of a divorce, especially if Charlie signs another seven-year contract with the Hoff-Federated Studio. That studio's head, megablowhard Stanley Hoff (a completely over-the-top Rod Steiger), is putting pressure on Charlie to sign, despite the fact that Charlie hates the quality of the studio's pictures. The wife of a studio flunky (Jean Hagen, who many will recall as the vocally challenged Lina Lamont in "Singin' In the Rain") is cornering Charlie into having an affair, while a former galpal of Charlie's, Dixie Evans (a small but fine performance here from Shelley Winters, who also appeared in such classic films as "Night of the Hunter" and "I Am a Camera" that same year), who has knowledge of an old Charlie Castle scandal, is now threatening to tell all. And perhaps most distressful, Hoff's right-hand man, Smiley Coy (the always dependable Wendell Corey), has come up with the perfect method of silencing Dixie for good...one that, unfortunately, entails homicide! Is it any wonder, then, that poor Charlie--who, as our narrator tells us at the film's opening, is "a man who sold out his dreams but can't forget them"--seems to be on the verge of a mental collapse...."The Big Knife" is the sort of film that plainly reveals its origins as a theatrical production. The entire picture--with the brief exceptions of a beach scene, a 60-second party sequence at a neighbor's house, and a short conversation at the studio--transpires in and around Charlie's Bel Air home, most especially in his sumptuous living room. Characters enter, interact with Charlie, depart, and are replaced by others. But despite the film's staginess, director Aldrich does a fine job at keeping things moving, and at eliciting wonderful performances from all his players. (Aldrich had quite a year in 1955 himself, what with this film and the future cult item "Kiss Me Deadly," which had been released in May.) Steiger, here in his third picture, and shortly after his memorable demonstration of acting ability in the previous year's "On the Waterfront," is an especial standout, investing his Stanley Hoff with borderline monomania as he alternately bellows at Castle and menacingly purrs lines such as "I'm going to have to take this very much amiss." A seething mass of self-made philistinism with a blonde dye job, the character surely does make some kind of impression on the viewer. And as for our antihero, Charlie, Palance might prove a revelation for some; a raving tough guy, sure, but one whose yearning for something better, whose disappointment with what the Hollywood dream machine has handed him, is clearly discernible in his tortured eyes. The film sports any number of hugely dramatic scenes (every single one of them, come to think of it) and an adult, literate script by James Poe (future husband of Barbara Steele, the lucky bastid!) featuring many quotable lines of priceless dialogue. I love it when Castle's agent, Nat (a very fine bit of acting here from Everett Sloane), tells Charlie, "Business and idealism...they don't mix." And when Marion's current beau, Hank (Wesley Addy), tells Castle that "half idealism is the peritonitis of the soul." Or howzabout this line, as Castle speaks of his current life: "This is all a bleak, bitter dream...a real dish of doves"? The entire film is like that, filled with impossibly sophisticated dialogue and tense confrontations. Ultimately, the picture leaves the viewer quite sad, and with virtually every character in a worse situation than when the film started. Just another couple of weeks in the Dream Factory! All told, "The Big Knife" (and I can only assume that the title refers to Hollywood itself, which certainly seems to cut and separate more effectively than any Henckels blade ever could) is a very impressive affair. My only complaint: the oftentimes intrusive musical punctuations by Frank de Vol, unnecessarily offering up a "bom-bom-bom" whenever someone says anything overly dramatic. Too bad a big knife of the Moviola variety couldn't have been used to excise these snippets from what is otherwise an exceptionally fine film....

RResende

By coincidence, I saw Carnage, the new Polansky, shortly after this one. Polansky is a master of small spaces, and moving inside them, and making them part of the dramatic fabric of the film. Space as drama, as metaphor, that's one of the things that made me want to watch films seriously, one of the concepts dearer to me. Robert Aldrich is also a spatial man, a cinematic architect, who also considers and bends the space to take from it wherever he is making out of the material he is shooting. That's specially well done in Kiss me Deadly, a must-see on many levels, but also here in this smaller film. Here we have filmed theater, a one set film. The first problem is that the set is a little bit studio like, and thus is more contrived, giving Aldrich less possibilities for breaking the camera angles and camera moves. Shooting studio was norm, and had advantages, light control, etc, but the downfall proves bad for the kind of visual work that Aldrich liked to try. Well, it's a little bit like Palance's character, trapped inside his golden cage, living profitably at the expense of artistic compromise. But this film is still a worthy experience. The text helps. The inner tensions of Charles Castle, mapped into Jack Palance's own Method approach to acting. All that wrapped about the brilliant vision of Aldrich, supported by the also brilliant Laszlo, a fine cinematographer, we have such great films produced by his camera. This is a one space film, but also a one-man show. It's all about how the environment mirrors how Palance reacts to the world. In that sense this is a kind of noir, in how he only reacts to the adversities, a pawn in an odd world, where he is the odd center. But this is not noir in the wider sense, in the definition that Ted applies to it, which i embrace. Ida Lupino was a clever artist, and she knows enough to support Palance's act. She really helps. We tolerate Steiger's excesses because his character is not too much exposed, but he does go over the top.Anyway, stick to the camera, how it reacts to Palance. The characters movements, what's usually defined as mise-en-scène, is remarkable in how it is reflected always in how the camera moves. This is something that started with Hitchcock's Rope. Sidney Lumet toped this game with his Angry Men, but this is a sensible use of the camera in that respect.My opinion: 3/5, a very pleasant minor work of a very fine director.http://www.7eyes.wordpress.com