Perry Kate

Very very predictable, including the post credit scene !!!

Breakinger

A Brilliant Conflict

Lidia Draper

Great example of an old-fashioned, pure-at-heart escapist event movie that doesn't pretend to be anything that it's not and has boat loads of fun being its own ludicrous self.

monchinglopez

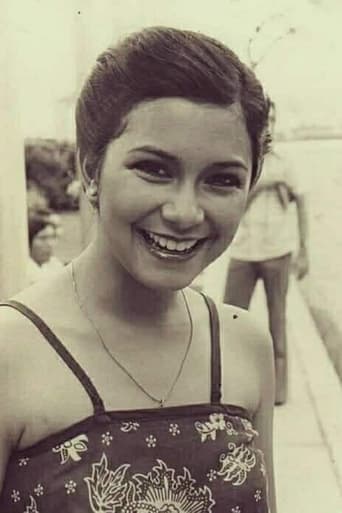

Before anything else, it should be made clear that this review was made comparing the film to the original text which it was based on. The Summer Solstice, a short narrative by Nick Joaquin is genius and powerful, clearly a timeless masterpiece inspired by the greatest of muses. But sad to say, the film adaptation of the short story entitled, Tatarin is seriously lacking in depth and quality which makes it easily forgettable. From unforgettable to forgettable. This was how much the film adaptation ruined the narrative. Nick Joaquin's story was effective in portraying a eulogy to a man-driven, pseudo-American Philippine society, while its film adaptation directed by Amable Aguiliz was confusing. Despite being backed by Viva Films, one of the major production machines to ever grace Philippine cinema, the film still succeeds to end up a miserable undertaking, light years away from being a timeless classic that Nick Joaquin's story is. Tatarin was an entry to the 2001 Metro Manila Film Festival but to my knowledge it failed to bag a major award in the event. And rightfully so. For starters, the film was filled with a roster of newcomers to the silver screen, most of them were sexy stars. I have nothing against neophyte actors, actresses or sexy stars but putting them in a material possessing enormous potential was not a very good idea as proved by the finished product. Much of the film's lackluster acting should be attributed to them. I think the producers and the director should have chosen from a pool of seasoned actors and actresses in the country. But then again, choosing an actor also depends on the roles available. The scriptwriters and the director added and modified some characters from the original text which made it difficult to cast veterans. One such example can be seen in the Moretas' house aids. In the original text, Amada was not a young vixen that Rica Paralejo is. Then again, the director and his crew always have the freedom to modify the original narrative whenever they deem it necessary. It is only an adaptation after all. Of course the next question would be: was the particular change necessary? This is where it gets tricky and contentious. This also serves as an argument supporting my comparison of the short story and its adaptation.I really do not think that transforming Amada and the rest of the Moretas' house helpers into sexy, young, erection inspirations was done to better the original text. If someone watches the film without reading the text and sees the scene wherein Guido asks Lupeng about Amada, he or she would likely think that it is only natural for Guido or any man to be enchanted by Amada since she was portrayed by a woman in her mid-twenties with a voluptuous body. But credit should also be given to the fact that Amada was a Tadtarin that day. This is what I mean when I say that the film adaptation was confusing. On the other hand, Amada as written in The Summer Solstice was stout and elderly. Thus when Guido asks Lupeng about her it was clearer that her enthralling appeal was because she was a Tadtarin. Why then was Amada modified for the adaptation? An endless number of answers or opinions might surface but I feel that this has something to do with the cast of breast-baring sexy stars who comprise much of the Moretas' household. The film was not made for art's sake. It was made to sell. And the moderate sexual content included in the film, enough to garner it a R-18 rating by the way, proves just how much it depends on sex to sell tickets.

Noel Vera

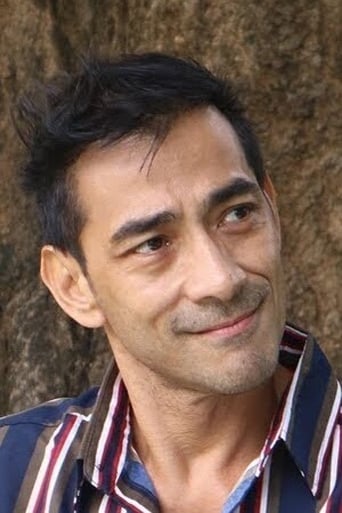

There are at least three entries in the 2001 Metro Manila Film Festival that seem meant to be taken as actual quality fare: Tikoy Aguiluz's "Tatarin" (Summer Solstice); Joel Lamangan's "Hubog" (A Woman's Curve), and Marilou Diaz Abaya's "Bagong Buwan" (The New Moon).The standout by far among the three, I think, is Tikoy Aguiluz's "Tatarin." Based on Nick Joaquin's play "Summer Solstice," the film is about the oldest and longest-running war known to man, the war between the sexes. Joaquin's problem then was how to make this war relevant again to jaded audiences (the play was written in 1975); his solution was to set the play in the 1920s, when male-dominated Western Culture was just beginning to tremble. Aguiluz's adoption of Joaquin's stratagem is, I think, a smart move--this way he captures the very roots of the war (or at least of the 20th century edition of the war) as waged by our grandparents and great-grandparents; he photographs the combatants at a time when the battle is still urgent and raw, the stakes desperately high.And the battle lines are drawn, of course, around a married couple—Don Paeng and Dona Lupe Moreta (Edu Manzano and Dina Bonnevie), on the evening of the Feast Day of St. John the Baptist, on the third night of the "Tatarin"--a pagan ritual where for three days out of the year women hold ascendancy over men.I can't think of a better Filipino filmmaker than Aguiluz to evoke the living past--especially in a production like this, where immersion in a long-gone age is crucial to the success of the film. Combining the considerable resources of Viva Studios (which are usually poured into banal glamour productions) with his keen documentary filmmaker's eye, Aguiluz (with the help of production designer Dez Bautista) evokes the remarkably authentic, miraculously detailed world of the Moretas--from the flour mill that produces their dried noodles, to the 1920s-style kitchen hard at work on dinner, to the luxuriously appointed family mansions with their incredible painted ceilings. And it's not just a matter of having an enormous production budget; it's the intelligence to pick out this particular detail, the wit to shoot from that particular angle--then the judiciousness to cut it all up so that you only glance at the images, and are left wanting more.But more than the ability to recreate a historical period, Aguiluz (again, with the help of writer Ricky Lee and editor Mirana Medina) is able to streamline Joaquin's play, to focus on the struggle between Don Paeng and Dona Lupe. The three have tinkered with Joaquin's married couple, made delicate adjustments, crucial revisions--the Moretas, for one, have lost all warmth and affection for each other, where in the play they still show signs of tenderness. Don Paeng has become a psychologically immobile, sexually impotent monster (kudos to Edu Manzano for the courage to portray such a thoroughly unlikable man) while Dona Lupe (Dina Bonnevie, in possibly the performance of her career) has become more submissive, more withdrawn (the better to highlight the climactic reversal when it comes).Then there is the dialogue, which has been pruned, made less explicit, made more functional than decorative. Besides the careful pruning, Aguiluz manages to locate the drama in the moments when words are not spoken--through shots that encapsulate in a single image the tension of the scene, like the one where Dona Lupe's foot is kissed by Guido (Carlos Morales), with Don Paeng watching from the balcony. Don Paeng, the shot says to us, is ascendant by virtue of his standing in the balcony, but is also rendered remote and helpless by the distance.Then the "Tatarin" ritual itself. Moved offstage in the play, the ritual occupies center stage in the film: a wordless, ten-minute orgy of pulsing drumbeat, flaring torches and convulsing women. Aguiluz wanted the sense of a real location turned theater set, and he got it--the dance, staged at the foot of an actual balete tree, feels nightmarish, surreal. And obscene--though nudity is at a minimum, there is no lack of lewdness to the drumming and dancing, which at times is reduced to frank rutting. "Pagan" is a polite and inadequate term for what happens at the foot of the balete tree."Tatarin" feels more lighthearted than Aguiluz's earlier works, if only because he doesn't end the film with a life-or-death situation (meaning: the protagonist didn't die). More, it's the first really comic film Aguiluz has ever directed, and he handles the material with admirable lightness and vigor. One of the best Filipino films of the year, and my vote for best of the festival, hands down.

Eide Cravine

The masterpiece of National Artist Nick Joaquin, the "Tatarin" is a depiction of the 20s. It presented the ancient pagan dance ritual, known as the "Tatarin" itself, which is celebrated on the same day coinciding the feast of St. John the Baptist. It started out in a period of play production but with the technology of cinema, it has been turned into a motion picture by a great director namely Tikoy Aguiluz and had been scripted by Ricky Lee for Viva Films. Another National Artist namely Lucresia Kasilag (for music) composed the music. Edna Vida of Ballet Philippines choreographed the dance rituals and Dez Bautista was tapped as production designer for the period setting. Well, I had to pay attention to these bits of information anyway. I just watched the film in order to make a movie review again and the text here is what I passed to my professor. I am not going to watch a bold film anyway if I am not required to."Tatarin" used the backdrop of the American occupation, the period where the picturesque "Tatarin" ritual awakens the goddesses in the quiet, passive spirits of a mistress of a mansion, Lupe (Dina Bonnevie) and her maid Amada (Rica Peralejo). Drawn to worship of a centuries-old Balete tree, Lupe and Amada are caught in a trance that liberates them from all their inhibitions. Through ceaseless chanting, Lupe and Amada empower the weakest of their sensibilities. And by some form of erotic pagan dance, they rouse to frenzy the most savage of their desires that from long ago, had been chained up to frigidity by men who dominate their world. There is a distinction between the male and the female sexuality then in this film that has been shown. Also, there was the ritual of water. This is done by literally wetting people, even if they are just walking on the road. During the 20s-40s, this ritual has a little sexually related meaning giving stimulation to the watching males on the females in the procession. These females were the ones who were subject to the "Tatarin-soul transfer." They join the procession of the males that attracts them but the females later go back to a hidden place where they started doing their dancing accompanied by their hallucinations and desires. In the evening, they go back to their husbands and prefer doing sex.The film is a little "libidinous" in a more complex sense than what merely culminates in bed, or any other explosive location-to go by movies these days, the bed is now the least preferred one. Lupe and Paeng (Edu Manzano) is a 1920s couple straddling two worlds, the worlds of dark and light, sun and moon, day and night. It takes place during the time when the world is equally divided into day and night … hence, the title. It is also a time when the sun boils at day and the moon burns at night, which makes for oppressive heat. The characters in the story keep talking about that heat, which gives it all sorts of resonance … and males still dominate over females. Beyond the literal, Lupe and Paeng straddle the worlds of a Catholic present and a pagan past, a present that exalts manhood and a past that worships womanhood, a world of rules and convention and a world of instinct and primal drives. This shows the setting of Nick Joaquin's story then.On the day of the Tatarin, all their dreams are believed to come true. Mothers without kids, a girl wishing her unfaithful mate to come back, an old lady wanting to restore her beauty, and a woman dreaming of the man she loves … all of them pray and wish and offer sacrifices for the Tatarin. And coinciding with the Feast of St. John, females are unstoppable. She dances the power of a woman - the meaning of the Tatarin … like a knife of a butcher; this is a weapon of women against men. The aim of the women is to make all men follow what they desire. (The moon as the queen of the females - ruling the night and covering the day.) If you try to stop them, a plague will somehow rule the land.Lupe's descent-or ascent-from the first to the second, a tilting of the weight from the one to the other restores balance between heaven and earth. This happens during the Tatarin, the Philippine version of a druidic festival or rite, which itself fuses two seemingly contradictory worlds. The Tatarin, a pagan festival, culminates on the feast of St. John, who is not just a definitely Christian symbol but also a thoroughly masculine one. In the end, Paeng, the master, pleads in the dust before his wife, ready to kiss her feet and become submissive. One line justifies it and it goes: The moon becomes as bright .............. as the sun.

clarencehenderson2003

HALO-HALO CULTURE AND PAGAN RITES Set in the 1920s, the film tells the story of a couple caught in the juxtaposition of Catholic/Hispanic value systems and the pagan rituals that existed long before Magellan set sight on Cebu. The Tatarin is a uniquely Filipino version of a druidic rite. During this surreal ritual, which takes place during the feast day of St. John the Baptist, normally repressed women transform themselves into "Tatarin" - enchantresses and witches. They gather together to worship the centuries-old balete tree, which sets them totally free from inhibitions, empowering them to dance erotically while the men (who normally per macho Hispanic tradition completely dominate them) watch helplessly. Symbolically, this suggests a theme of balance, with man as Sun and woman as Moon - and about the imbalance brought about by the externally imposed values of the West. The ritual reflects, like many pagan rites, the vital importance of maintaining balance between heaven and earth, an essential balance for ensuring healthy lives, avoiding devastating wars, and raising good children. When things get out of balance, terrible things happen. In pre-Western Philippines, the Sun (male) represented the Supreme God (known by Kabunian and other names). But equally important was the feminine moon, wife of the sun. The cycle of sun and moon ensured balance, much as yin and yang do in other Asian traditions. These dichotomies are captured elegantly in Tatarin, which has as one of its primary themes an oppressive heat symbolizing elemental passions always on the verge of exploding. The movie has many images of the sun boiling in the day and the moon burning hotly during the night. There is a great deal of repressed libido here, captured in the Filipino term libog, which basically means the state of being horny. Paeng, the masculine and aloof husband (played by Edu), sees the ritual as silly and old-fashioned, suitable only for the indios. His wife, played by by Dina Bonnevie, embraces the ritual as a long-sought after channel for self-expression (and orgiastic release), something totally foreign to Catholicism and the repressed sexuality it brought with it. Ultimately, Paeng ends up crawling in the dust in front of his wife, ready to kiss her feet now that she has finally asserted herself as a woman. Aside on libog: When asked to interpret his work, Joaquin reportedly replied: "It's all about libog, isn't it?" To illustrate the use of the term, consider the following three versions of the phrase "you're making me horny": Tagalog: Nalilibugan ako sa iyo; (2) Taglish: You're making me libog naman; (3) English (sixties version): Why don't we do it in the road?