Mjeteconer

Just perfect...

KnotStronger

This is a must-see and one of the best documentaries - and films - of this year.

Aubrey Hackett

While it is a pity that the story wasn't told with more visual finesse, this is trivial compared to our real-world problems. It takes a good movie to put that into perspective.

Billie Morin

This movie feels like it was made purely to piss off people who want good shows

WILLIAM FLANIGAN

Viewed on DVD. Restoration = six (6) stars. This movie can be an acquired taste, but the viewer must be extremely patient during the acquisition process! Overly long due to interior/exterior visual padding and foot-dragging direction, it nonetheless exhibits: some fine acting from many contemporaneously well-known actors and actresses; a well constructed script with many red herrings, twists, turns, and moments of great dialog (plus a phantom major character); plenty of location shots (including the Kiyomizu-Dera Temple and the stone garden at Ryoan-Ji in Kyoto which pretty much look the same today); good sound; and clearly-enunciated line readings. Subtitles are right sized. Except for an occasional pan of sea waves or fields, cinematography is spot-on static. All action occurs within the frame (like viewing a stage play). Even for close-ups on bikes! However, camera placements are imaginative and lighting is well done. On occasion, the director films the backs of speaking actors when the viewer would expect expressive frontal shots. This "back acting" is interesting, but a bit disconcerting (especially when a back-acting shot is immediately followed by a duplicate front-acting one). Music lacks imagination in composition and film placement. It is monotonous (there is essentially only one Leif motif played over and over) and often inserted into the sound track in an amateurish manner. The serene, apparently economically-secure, middle-class society depicted here did not yet exist, and seems to have been offered up by the director as a proper modern and attainable objective (which was reached by Japan in an incredibly short time thereafter!). Semi-restoration leaves behind wear lines, frame jitters (especially during the opening credits), and age-related deterioration during dark scenes. WILLIAM FLANIGAN, PhD.

Lilcount

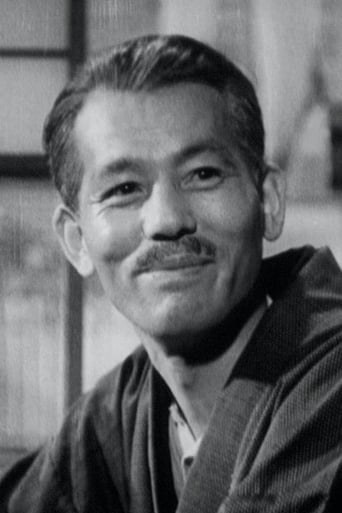

It is one of those strange coincidences that occur in life that on the very day the passing of Japanese acting legend Setsuko Hara is announced, the world premiere of the digital restoration of one of her greatest films, "Late Spring," happens at MOMA in New York.The restoration is a godsend to those who have seen this film only in poor quality circulating prints. There is no more flicker, no more warpage. One of Yasujiro Ozu's greatest achievements now looks the part.Words cannot do justice to the magnificence of Setsuko Hara's performance as Noriko. Her face and eyes convey her inner torment as her perfect existence is shattered by society's, and her reluctant father's, demand that she marry.Near the end, Noriko is shown in a mirror in her wedding kimono. Her smile never wavers, but her eyes reveal her despair. Hara's work here is one of the few performances to rival Falconetti's in Dreyer's "La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc."But Ozu does not neglect Chishu Ryu, whose last scene is heartbreaking.This film is a minimalist "Vertigo." That is to say, it's one of the greatest films ever made.

Robert J. Maxwell

The director, Yosujirô Ozu, had a reputation for never moving his camera. I didn't notice movement in "Tokyo Story" but wasn't looking for any. This time I tried to keep track of any camera movements, not including source motion, as when the camera is fixed to a moving train or a bicycle. I only counted one. For a few seconds, Ozu's camera trundles along behind a couple riding bicycles down a lonely road. There are times when the camera remains stationary after the actors have left the screen. I began to wonder if maybe Ozu didn't know HOW to move the camera in a mechanical sense, hand-held, dollies, and so forth. But then I recalled that in Peter Yates' "Bullet" there was only one dissolve, and all the rest of the editing consisted of cuts.Okay. So it's a matter of personal style. And I'll take this opportunity to advise anyone who enjoys movies like "The Bourne Ultimatum" to avoid "Late Spring" at all costs. If they were to try sitting through this movie -- a little grainy, in black and white, with Japanese subtitles, subtle, and an immobile camera -- the results might be tragic. They should remember that a person in shock should be placed in the Trendelenburg position with the feet elevated between 15 and 30 degrees above the head.The movie? Oh, the movie. We get to meet a beautiful and expressive Japanese woman of twenty-seven years (Hara) who lives with her fifty-six year old father (Ryû) and takes care of him. She's perfectly happy with the arrangement and so is her father, until a relative suggests that a marriage be arranged between a nice young man and Hara. Being married when you're almost thirty is rather a late spring.Well, Hara has a smile that lights up a room and a nature that complements it. But when her father brings up the prospect of marriage, her face falls and her animation bleeds out of her. It isn't so much that she doesn't want to be married. It's that she desperately wants to continue living with Ryû. He can't care for himself. "He burns his rice." Carl Jung would introduce the Electra complex at this point but I think we can safely skip it.She and her father take a vacation to Kyoto, where we see some impressive scenery, man-made and natural, which resemble picture postcards, given the immovable camera. Father and daughter have a long talk and Ryû, whose conversation so far has mostly been limited to "Hmmm", which carries several meanings, tells her that happiness is the result of time and effort, that he didn't love her mother when they were married, and that in fact he's decided to marry a woman who is an acquaintance himself, so Hara has nothing to worry about. She still has doubts but now she has hope too.But Ryû has lied to her. There is no marriage in his future. The young couple are married and leave. After the reception, Father has a few cups of saki and walks home. Sitting alone in the now quiet house, he begins to peel an apple. It's a long, single peel that finally drops to the floor, bringing back some jokes that Hara used to make about not being able to slice pickled radishes. Ryû sits for a moment before dropping his gaze. It's a touching moment because, for the first time, we realize how much unspoken love he felt for his daughter, how much he will miss her presence, the weight of his sacrifice, the bleakness of his own future.All of which goes to demonstrate that you don't need to wobble the camera around in order to make a gripping film.

commanderblue

"Late Spring" is Yasujiro Ozu's stunningly poignant portrait of a 27-year-old daughter who lives with her 56-year old father in post-World War II Japan. A film with a deeper meaning than its simple story implies, "Late Spring" is like the neorealist version of Japanese films, in that it tells a story larger than life with few but memorable characters.Another spring comes to a little town not far outside of Tokyo, Japan. At the same time another woman is getting married and Ozu opens up with a marriage ritual with beautiful women garnered in kimonos as the ceremony unfolds. Outside the wind gently blows and sways the leaves and trees back and forth. The flowers are in bloom. Ozu makes it clear that marriage is not just a ritual but a tradition like the seasons.The central character is Noriko, a 27-year old unmarried woman who lives by her father's side. She knows him just as well as he knows her, and Ozu creates a humble home environment through their natural interactions. "I'm home!" Noriko will announce. "Have you had anything to eat yet, Father?" Noriko, we discover, not only feeds and cleans and cares for her father but occupies a very important hole in his life. This is more than a father and daughter relationship but one that thrives without a mother figure. Ozu never reveals the cause of her death, but this is a daughter without a mother and a husband without a wife. For that, they are inexplicably bound.Noriko's Auntie always attends the nuptials and sees it as the time for Noriko to be married. She cannot be blamed for this. The Aunt, a widow herself, is a woman bound by tradition and thinks if her niece avoids marriage any longer her chance of a fruitful, wholesome life shall be tainted (hence, late spring). The Aunt almost urgently wants Noriko to marry. For Shukichi, the father, letting go is a little harder.Noriko is unmarried but not without a social life. On weekly commutes to Tokyo she meets up with Mr. Onodera, a family friend. Often, they'll window shop together and finish with shots of sake while Noriko gently but wittily quips about Onodera's second marriage. Noriko is also friends with Mr. Hattori, her father's young work assistant. Hattori could be a potential husband, and they get along fine biking down the beach together, except Hattori is engaged to be married and that's the misery of it.Lastly, there's Noriko's friend, Aya, who came from the same educational upbringing but married earlier in life. Aya has experience which is not so much an advantage over Noriko but something more to talk about. "I don't want to get married," Noriko says and Aya is appalled. Aya argues her divorce only made her stronger. Noriko sees this as a weakening of the human spirit.Setsuko Hara, who plays Noriko, is not only a beautiful woman but a fine actress. She smiles ear-to-ear throughout the picture and it's amazing that somebody could look so happy. Only when there's talk of marriage does that smile begin to dissipate and Noriko ruefully laments she'd rather have an eternity with her father. "You don't find happiness," her father says. "You create it." Marriage is unique because for every bond that's joined another is broken. "Late Spring" testifies to that, and it tells it so well, without superfluous sentiment, that the result is a picture so compelling it touches the deepest corners of our hearts.