ThiefHott

Too much of everything

Gurlyndrobb

While it doesn't offer any answers, it both thrills and makes you think.

Clarissa Mora

The tone of this movie is interesting -- the stakes are both dramatic and high, but it's balanced with a lot of fun, tongue and cheek dialogue.

Roxie

The thing I enjoyed most about the film is the fact that it doesn't shy away from being a super-sized-cliche;

bkoganbing

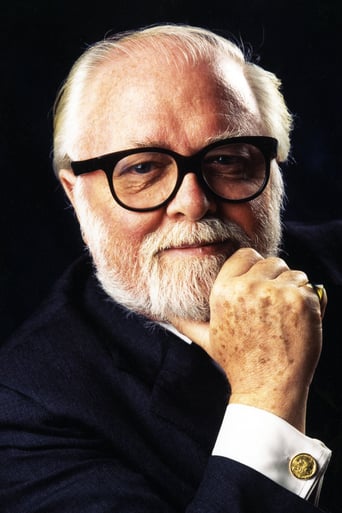

In 1957 with the independence of the Gold Coast renamed Ghana as a new nation, the various colonial powers were getting shed of their colonies as World War II left them unable to hold on. If you looked at a map of the world the year before you would see in Africa the various colonial entities depicted in the same color as the power holding on. By the end of the Sixties you can see Africa as color coded without reference to a mother country.This phenomenon started for the British when they left India to her own devices in 1947. It started with Ghana in 1957 and Guns At Batasi starts as a scene being repeated over and over in Africa, British regular army forces packing up and turning their military installations over to the new African armies of whatever country they were in. But there's a bad political situation brewing here. The Africans that the British have turned the country over to are now being threatened themselves by a military coup. As RSM Richard Attenborough and his mates are just enjoying some last hours at their Sergeant's Mess, wounded Captain Earl Cameron seeks refuge. His lieutenant Errol John is part of the new government and he wants Cameron as a war prisoner.There's a bit of racist attitude in Attenborough and his peers, but they have been in Africa for years and know the temper of the people. A great deal more so than Lady MP Flora Robson who knew Errol John as a student in London and feels she can reason with him. She gets disabused of that notion rather fast.It's a delicate political situation that Attenborough doesn't need reminding of. Still he shows some good initiative in his response.Guns At Batasi is a snapshot in time of the changing face of Africa. And even more interesting is the fact that the film was shot in the United Kingdom without setting foot in Africa. The producers could get away with it because most of the film takes place in and around the sergeant's mess. And Africa was replete with Batasi like incidents to make location shooting not a good idea.Although he's backed by a superb cast which also includes Jack Hawkins as the local army commander and Cecil Parker as the former colonial administrator of the area, Guns At Batasi is the film of Richard Attenborough. He really does become the spit and polish, all army RSM. It is said that the high non-commissioned officers really run the army in an country and with people like Attenborough you can believe it.Errol John is wonderful in his role as well. A few years earlier this was a part earmarked for Sidney Poitier, but now many black players were getting their due. John should have had a great career.Guns At Batasi is a great film about the declining days of the British colonial empire. This was when the sun was finally setting.

Robert J. Maxwell

I never believed that I would ever see Richard Attenborough in a movie in which he seemed to be overacting. I mean "Attenborough" and "overacting" don't belong in the same sentence. Yet here he is, as the Sergeant Major left in charge of half a dozen non-commissioned officers at a British Army post in Africa, the highest rank an enlisted man can achieve, and he enacts a blustering stereotype, his mess hall accent full of roller coaster contours.Actually I didn't mind it too much. Make up has aged him, given him and intense, almost crazed look, and the director, John Guillerman, seems to have given Attenborough his own leash, and Sir Richard takes off with it. He's a bundle of fiercely constrained potential energy. He never walks. He strides. He snaps out orders to African and British soldiers alike. He insists on proper decorum. He will not recognize an African colonel who has just taken over the country and is threatening to destroy the British post with 40 millimeter cannons -- until the infuriated colonel removes his cap in the mess hall. First things first.It's mostly a filmed play that takes place in the Sergeants' Mess, and it looks it. There are a few outdoor scenes but they're brief, and mostly filmed at night.The performers all look properly sweaty. They're competent too, though none stand out except Attenborough and a few scenes with the ever-reliable Jack Hawkins, who breezes through his part in a state of quizzical tranquility. The women -- Flora Robeson and the teen-aged Mia Farrow, are mostly along for the ride. Farrow looks plumper, more succulent, than we're used to seeing her.The story is fairly comic at first, concentrating on the men's resigned acceptance of Attenborough's by-the-book military character. When he spins a tale at the bar, the other men can mouth the story silently word for word.He performs an heroic deed at the end, but unknowingly he does it after the conflict is resolved. At the request of the new African president, Attenborough is sent back to England. He's not reprimanded or court martialed but it's a definite slap in the face, considering what he accomplished. Later, alone in the mess, he flings a glass of whiskey at the portrait of Queen Victoria, then hurriedly tries to cover up signs of the deed. The significance of the act may have escaped me. I'd have to guess that he, who has lauded the British Army from the beginning, feels that it has turned on him, and that Victoria represents the Army. Instead of a decoration, he's gotten a boot in the pants. If that isn't why he hurls the glass at the picture, I don't know what it is.It's not a bad film and I realize Richard Attenborough has received a cornucopia of kudos for his performance, but it's still a stereotype, a kind of Colonel Blimp. This was shot in 1963 when the British Empire was in the process of contracting and it occurs to me that it might seem dated now, except that as this is being written, the United States is having an almost identical problem in Iraq.

tieman64

"Mr. Boniface! I've been a member of this Mess for 23 years, Sir. In all that time I've never seen anybody - man, woman or child - walk into this mess with his hat upon his head. I do not see you now, Sir!" – Major Lauderdale (Richard Attenborough)Shortly after World War 2, the British Empire, once the largest Empire in all of World History (at one point holding sway over ¼ of the world's population), began granting independence to many of her oversees colonies. This period of decolonisation began in 1945 and ended as late as 1997, though by the early 1980s the yielding of independence to Zimbabwe and Belize meant that most of the major colonies had been set free. This freedom came at a "cost", and wasn't entirely benevolent. Britain did her best to destabilise and divide these colonies before departing, and retained control of as many local industries and institutions as she could.With the dismantling of the Empire came a wave of films, during the late 1950s and early 60s, which were openly critical of colonialism ("The Hill", "Battle of Algiers", "Z" etc). "The Guns at Batasi" belongs to this group, but is more interested in exploring the confusion that emerges when a country is granted the right to self-determination.Set in a military outpost during the last days of the British Empire, the film revolves around a by-the-books Regimental Sergeant Major, played by Richard Attenborough, caught between two dissident factions in a newly-created African state. The film highlights how many post-colonial governments are overthrown by populist rebel groups, and how the process of decolonisation often creates a period of violent turmoil, different factions rising to occupy the vacuum that the Empire once filled. But unlike films like 1959's "North West Frontier", "Batasi" isn't interested in "praising" the Empire for keeping order (this "order" came at a horrible price- millions dying across the West Indies, for example, and almost 1.8 billion in the Indian colonies etc). No, the film is instead obsessed with the far-ranging identity crises that often occur during specific types of social unrest. For example, Richard Attenborough plays Major Lauderdale, an ultra-patriotic disciplinarian who with the collapse of the Empire now seems like a 19th Century anachronism. Like an emasculated man desperately holding on to outdated codes of masculinity, honour and nationalism, Lauderdale is continually mocked behind his back by both his officers and a liberal female MP. Lauderdale's inability to adapt to this "brave new world" is mirrored to the numerous African officers he encounters, characters who likewise find it difficult to comprehend the freedoms they've been given.What eventual emerges is a film that is very critical of previous British values. Made during the height of the second-wave British feminist movement, the film ushers in an era of change, not by celebrating the freedoms and "liberations" of the 1960s, but by mocking the archaic world it has replaced. Attenborough, whose Major Lauderdale is one of the celebrated actor's finest creations, is thus an amplification of the kind of caricatural military man Alec Guiness played so well in "The Bridge Over The River Kwai", a cartoon whom we both chuckle at and sympathise with.What's most disturbing, though, is that after all these post-colonial films, most of which were openly critical of colonialism, British and American cinema began releasing a slew of films that began capitulating to certain imperialist tropes and racialized fantasies. In 1984 author Salman Rushdie commented on this trend, describing a spate of British productions (David Lean's "A Passage to India" and Attenborough's own "Gandhi" helped counter this somewhat) as "the phantom twitchings of imperialism's amputated limb". These were epics which are bathed in a kind of colonial nostalgia. They served as apologias for Imperialism, romanticised the native and offered up a kinder, gentler version of colonialism. Meanwhile, "the native", because he's portrayed as being "closer to nature" ("Out of Africa", "Indochine", "The Piano" etc), and thus less corrupted than his white counterparts, often acted as a symbol designed to redeems certain white characters (as well as the colonising culture that he is associated with). But made in the early 1960s, "The Gun's of Batasi" is a bit more complex and doesn't succumb to these later trends. "For the first time in the history of my country, Sergeant Major, it is the African who is putting the shell into the breech and giving the order to fire!" an African General yells, the native empowered by the white man's departure. But of course the white man is determined to retreat into history with his head held high. "I've never come across a misfit of your size and quality before!" Major Lauderdale responds, "If you do happen to go putting a shell into the breech, sir, I sincerely hope that you'll remember to put the sharp end to the front!" Witty spars like this are common in the film, the humour only dissipating when you realise that these African Generals are going to spend the next few decades killing their countrymen with British guns. "Who put the guns into their hands!" a female officer, seemingly the only voice of reason in the film, mourns. "You!"8.5/10 - An excellent film, which perhaps relies too heavily on dialogue to get its points across. Nevertheless, Attenborough's Major Lauderdale is such a cauldron of pent up emotion, that we can't resist watching his wild theatrics. Worth one viewing.

mphilipm

Richard Attenborough gave a performance in this film worthy of an Oscar and everyone in the movie shone. The writing, the direction, the experience are what movies are all about and time has not dimmed the significance of the content. It seemed to be a lost film for many years but has come out on DVD with the usual--and in this case--entertaining extras. It is billed as a "war film" but it is much more than that, an action film in the way in which Master and Commander is an action film, exciting but significant as well, since it illustrates a point of view with which you may agree or disagree but which you will see distinctly after a viewing, comparisons and contrasts being inherent to the vehicle itself. Mia Farrow debuted in this but it is an English movie with a fine supporting cast including Jack Hawkins in a final speaking role.