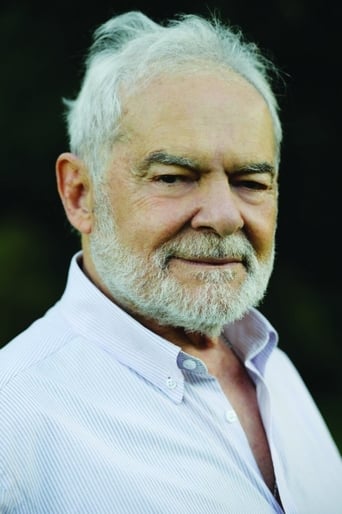

alexandre michel liberman (tmwest)

When we see most of the films about Jesse James and specially Sam Peckinpah's "Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid" we feel how difficult it is to define who is the "good guy". The outlaws are fighting the sometimes dishonest business interests of the politicians, railroads, banks, etc. Antonio das Mortes is the Pat Garrett of the Brazilian Northeast. His mission is to kill the bandit Coirana. They even have a fight holding a scarf between their teeth reminiscent of the Jesse James' films "Kansas Raiders"(1950) and the future "The Long Riders"(1980). But this "Pat Garrett" will realize he is on the wrong side and fight for his redemption. Glauber Rocha combines vivid colors with absorbing words, sometimes in rhyme, and rapturous folkloric songs. He expresses his views in the western format, as would be done later by Tarantino.

chaos-rampant

Okay so life is floating with shards of narrative, image, roles, history; obvious stuff that we all use to define self. There's nothing you can pick that doesn't entangle with threads going deeper, everything interdependent. The difference between lesser films and great is the first pick from the surface and arrange neatly into pleasant shape, diversions; great ones from deep within and disentangle the cluster, reveal our place. This is muddled as one review here says because it drags out threads from a corner of its own world, it falls on us to familiarize ourselves or not. Dated too, perhaps, because they're political threads we've left behind in their mess as no longer relevant and holding answers, so focus on the effort of revealing a tapestry. See here. A mountain bandit, last of his kind, and the bounty hunter hired to kill him, the place is a windswept plateau in a remote area of the Andes. But this is only the tip of the thread plucked from a popular folk legend in Brazil about bandits, as outlaws often are the subject of. Now see what the filmmaker pulls out beneath this, the bandit preaching to a poor mob about jailing the jailers and feeding the hungry, against oppression. It was I think Bakhunin who said brigands were the first true revolutionaries, outside confines. A revolutionary then, but in this context the subject of myth, of popular belief in a tradition of heroism. More entangling of iconography ahead. Instead of giving us a virtuous hero the way Soviets portrayed their Red Army officers and peasant heroes in the 1920s, he gives us a seething blowhard who proves to be below the heroic circumstances, as so often they do, fraying the symbol with life. No path is cut through oppression and yet it is his failure that inspires by revealing the extent of oppression. There's a lot of theatric writhing in all this, dissonant dances, cacophony, this is Rocha's way of fraying everything as he drags it out of pageantry to have life; not as special as Pasolini, similar aim. There's of course a corrupt mayor who has the town in a stranglehold with his stooges, another symbol of oppression this time, but not probed beyond its cruelty. No the real character who will have to brood over his place in a world and system where symbols prove to be small is the bounty- hunter, more reflection here. Rocha always questions, reflects in order to. But again how brilliantly he pushes out from the fabric images and iconography that question. The dead body is propped up on a tree as an icon anyway even if the actual person proved below the circumstances. The revolution does take place in the small village, the yoke of tyranny is overthrown, but what shape does it take? Rocha dips his hands in myth again and pulls out a whimsical western shootout with our hero shooting down dozens of henchmen, another iconic image, another narrative of popular belief. So a more esoteric subject whereas Pasolini and Herzog strive for cosmic miracle, but as profound and similar in the transformative tangle of reality and myth. I want to summarize Rocha here as I conclude my journey through his work with this. His main thrust is always political, not much interesting to me in itself. Ideals are rigid, mere devices on paper, hopeful signposts that turn rebirth into scholasticism. Rocha knows this, incessantly challenges both left and right, attacks the complacent views, demands an ambiguous life. Alert mind that uses politics to question politics, to question image, narrative, belief. So our worldviews are apart in particulars, he entangles the neatly arranged fictions, I'm looking into our ability to float free of fictions; but I'm glad to know him and always impressed by his ardor when our paths cross.

anithomas_d

this is one of the most beautiful films that i have come across. The beautifully changing styles of narration to get to a complete absurd or a rather dream like experience at the end of the film makes it one of the most beautiful essay on form. a must watch for anyone who is interested in understanding how a narrative style can change in the process of a film. glauber rocha is like a magician who brings out the pigeon from nowhere and turns into a rabbit and makes it into a formation of a cloud. it is pure poetry.The characters for Rocha are pure ideas, the movements and kinesics , takes them out of the fences of realism to the level of an oral narrative or a mythical one for that matter. As the movie progresses it turns, it can be best said, to take up the form of a folk dance.it is a normal phenomena to notice the drop outs in the first quarter of the film,before the turn over starts. the wrong perception created by the experiences of the various films that had ruled our viewings.at the end i will like to say it is a sure treat for anyone interested in the grammar and language of cinema.

milagrozo-1

If you watch Hollywood movies only, this one may be hard for you. But it will be a great experience for some lunatics (like me) who believe in the power and in the freedom of the cinematographic images.The subject is Brazil, the conflicts of a country that crossed a violent dictatorship at the time the movie was made. All the characters are representing groups of the brazilian society. Some of them, like the cangaceiros (poor and revolted people who became outlaws in the early 20th century), and the Saint (portrait of a blended religion that exists in Brazil, with elements of catholicism and african religions) are taken in a mythological approach. The delirious Glauber Rocha takes his characters to moral edges, leads them to crazy bang-bang scenes, to samba and war. There are no linear conclusions in the end. Only some new doubts and unusual beauty.