NekoHomey

Purely Joyful Movie!

Phonearl

Good start, but then it gets ruined

Konterr

Brilliant and touching

Solidrariol

Am I Missing Something?

gridoon2018

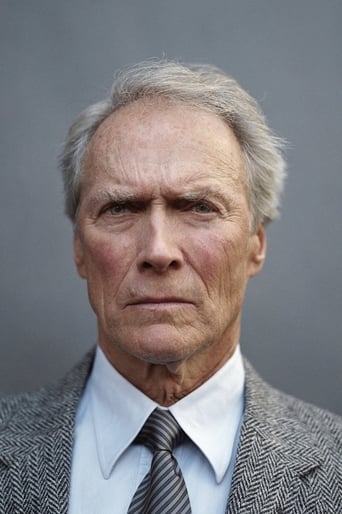

Martin Scorsese takes us on a journey through the history of American movies, roughly from the early silents to the late 1960s, though there are a few more recent pictures discussed as well. He does this with wisdom and insight, in a calm, soothing voice. Along the way, you get to relive some famous scenes from well-known movies, as well as discover films you had probably never even heard of. Of course any viewer might complain that their favorite movies are missing, but hey, that's why it says "personal" journey on the title, Scorsese makes it clear that he wants to focus on the films that influenced him and shaped him the most. One negative about this documentary: too many spoilers!! Otherwise, recommended to film buffs - when they have 3+ hours to spare. *** out of 4.

jzappa

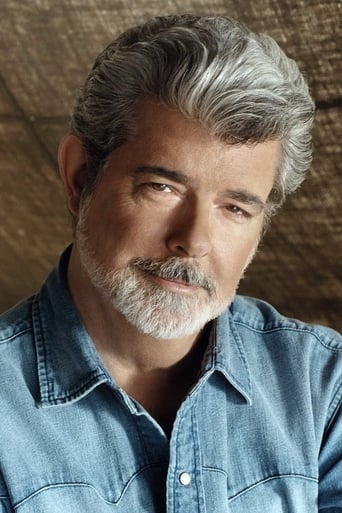

Prolific and highly influential filmmaker Martin Scorsese examines a selection of his favorite American films grouped according to three different types of directors: the director as an illusionist: D.W. Griffith or F. W. Murnau, who created new editing techniques among other changes that made the appearance of sound and color later step forward; the director as a smuggler: filmmakers such as Douglas Sirk, Samuel Fuller, and mostly Vincente Minnelli, directors who used to disguise rebellious messages in their films; and the director as iconoclast: those filmmakers attacking civil observations and social hang-ups like Orson Welles, Erich von Stroheim, Charles Chaplin, Nicholas Ray, Stanley Kubrick, and Arthur Penn.He shows us how the old studio system in Hollywood was, though oppressive, the way in which film directors found themselves progressing the medium because of how they were bound by political and financial limitations. During his clips from the movies he shows us, we not only discover films we've never seen before that pique our interest but we also are made to see what he sees. He evaluate his stylistic sensibilities along with the directors of the sequences themselves.The idea of a film canon has been reputed as snobbish, hence some movie fans and critics favor to just make "lists." However, canon merely denotes "the best" and supporters of film canon argue that it is a valuable activity to identify and experience a select compilation of the "best" films, a lot like a greatest hits tape, if just as a beginning direction for film students. All in all, one's experience has shown that all writing about film, including reviews, function to construct a film canon. Some film canons can definitely be elitist, but others can be "populist." As an example, the Internet Movie Database's Top 250 Movies list includes many films included on several "elitist" film canons but also features recent Hollywood blockbusters at which many film "elitists" scoff, like The Dark Knight, which presently mingles in the top ten amidst the first two Godfather films, Schindler's List and One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, and the fluctuation of similar productions further down such as Iron Man, Sin City, Die Hard, The Terminator and Kill Bill: Vol. 2. Writer Scorsese's Taxi Driver Paul Schrader has straightforwardly referred to his canon as "elitist" and contends that this is positive.Scorsese is never particularly vocal at all about his social and political ideologies, but when we see this intense and admittedly obsessive history lesson on the birth and growth of American cinema in both ideological realms, we see that there is really no particular virtue in either elitism or populism. Elitism concentrates all attention, recognition and thus power on those deemed outstanding. That discrimination could easily lead to self-indulgence much in the vein of the condescending work of Jean-Luc Godard or the overrationalization of the production practices of a filmmaker like Michael Haneke. Yet populism invokes a belief of representative freedom as being only the assertion of the people's will. As has been previously asserted about the all-encompassing misconceptions the people have about cinema, populism could be the end of the potential power and impact of cinema. One can only continue seeing films, because it is a vital social and metaphysical practice. And that's what Martin Scorsese spends nearly four hours here trying to tell us, something which can't be told without being seen first-hand.

T Y

Thre isn't a single Scorsese movie I'd place on a list of my favorite movies. But this is the best thing I've run through my DVD player in about five years. Scorsese's patient elucidation of favorite film moments, and how Hollywood works is incredibly gracious, calm and intelligent. It's 3 DVD-sides worth of material. It would have to be a British production, since everything about American corporate culture would have trampled the quiet, methodical, no frills, put-the-focus-on-the-content approach that is taken here. And an American production would have demanded he say he liked only movies that were popular favorites. I wish everyone took a page from his love of movies. You should love the movies you do for personal, idiosyncratic and specific reasons. Not just more "Me-too" votes for The Godfather, etc.. People have no clue what ideas are being explored in their favorite movies. If they did, movies would be more interesting than they are. Scorsese DOES know what ideas are being explored, and that makes him a compelling, involved speaker on the topic. I really appreciate his articulate, generous interviews over the last decade.On a negative note, Scorsese is best when he's excited to show you some obscure movie, rather than when he's didactically teaching you something well-established about film history. And I do wish he pluck those three hairs out of the bridge of his nose. It's very distracting.

tedg

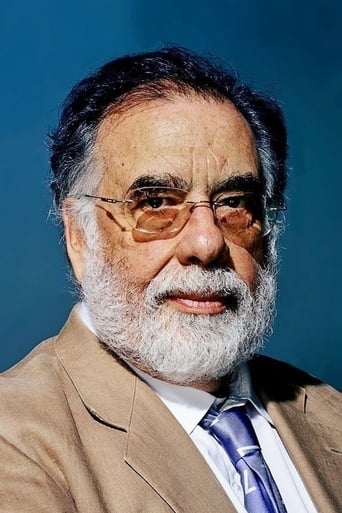

Spoilers herein.Popular culture plays a central role in inventing a life, the first tenet of which is choosing which sources to ingest. Scorsese is worthy of exposure: he is earnest and skilled.But the second law of conscious self-invention is a matter of which ideas and notions you cleave to. For me, Scorsese doesn't make the cut and none of his films are on my `worth watching' list, including this one.That's because Martin has a perspective on film that misses the real magic, the value. His review of important directors here clearly shows this. It is as valuable in revealing the cleft between him and others more creative as its intended purpose in `revealing film.'Scorsese believes film is a child of the theater and that the purpose of both is to allow us to explore the humanity of each other. His commitment to film mirrors his earlier commitment to the ministry. All his films can be clearly seen in this light -- and so can his `personal history' of film. Even the form of this documentary turns out to be an exploration of a single, interesting being. And the evolution from early films is traced in singularly one-dimensional path of human exploration to the latest evolution shown: the extreme Cassavetes. Cassavetes makes pure emotional `encounter' pieces.All well. But there are richer notion of film, and art. And life. These have less to do with the character of what we see than HOW we see it and HOW we react, probe. Who we are is more the issue, especially when encountering self as a process of the art.Contrast Scorsese to his peers dePalma and Coppolla. All of Scorsese's projects are anchored in the character. The camera is slave to the character. All action, indeed the whole environment revolves around the person, even emanates from them. His world of `Goodfellas' is a world of people surrounded by space that we passively watch and sometimes follow.Coppolla on the other hand lives in the visual assembly. His mind is situated not in the center of the character's heart, but in the filmmaker's hands. That's why we get cinematic effects of action in one place paralleled or superimposed on action in another, amplifying both. The drama is moved by the situation (mostly the visual situation) and the characters are just objects in the tide. It is very intelligent, this manner of composition. It is a little too mannered in fact for my taste, but it is intrinsically a cinematic art (both words emphasized), far from where Scorsese comes from.Or consider dePalma. He is something between and more clever. His projects are even more selfaware, and anchored by the camera -- the Eye. His eye places the audience not in a theater seat, but makes us God. We swoop into and around the action, abstractly separated from it. The camera has motivation and expresses curiosity, determination equal to that of a character. Coppolla creates montages after Eisenstein; dePalma, great eye poems after the manner of Tarkovsky.Take your pick. I prefer the narrative intelligence of dePalma, but both he and Coppolla know something about the magic of cinema that eludes mister Scorsese. Taking his work to be important art, the stuff one uses to form a mind, is a lazy decision.